)

Deep and dark web posts discussing malvertising and soliciting malvertising services are on pace to rise 68% this year compared with last.

In a malvertising attack, a threat actor deploys an ad via a legitimate online advertising network, such as Google or Bing. The ad lures the victim to a malicious website (possibly impersonating a legitimate site or service), which then tricks the user into downloading malware or revealing sensitive data.

This tactic has become one of the most popular methods to deliver malware. According to Securelist, the abuse of Google Ads--specifically sponsored search results listings--to spread malware has increased significantly in recent years.

In parallel, underground chatter discussing malvertising or transacting malvertising services has increased in recent years. Based on Q1 numbers, 2023 is on pace to culminate with over 2,700 malvertising-related posts, a 68% rise over 2022.

Figure 1: Number of posts that discuss malvertising services on underground forums

Figure 1: Number of posts that discuss malvertising services on underground forums

With malvertising on the rise, it is our understanding that the deep and dark web provide a growing venue for actors to buy and sell malvertising services as well as exchange TTPs and ideas.

Malvertising services generally involve the service provider posting ads to channel traffic to a landing page of the customer’s choice. Let’s take a closer look at actors selling and seeking malvertising services on the underground:

Services Providers

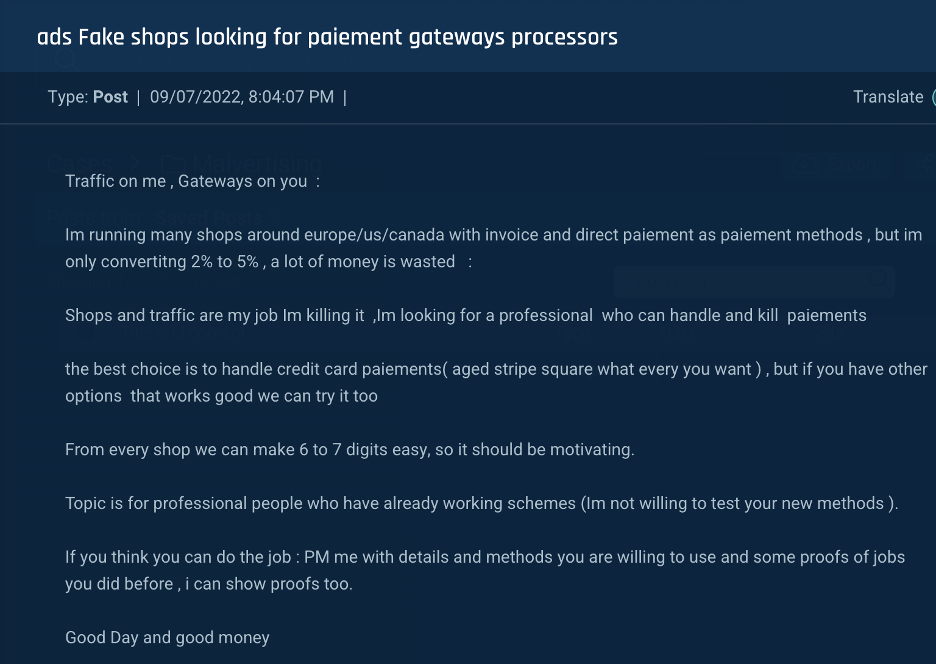

Threat actors advertise traffic direction services on underground forums (see figures 2, 3, and 4) or by commenting on posts from members seeking such services (see figure 5). While terms and conditions are generally discussed in private chats, actors occasionally reveal operational details. In the post below, the actor advertises fake shops and claims that partnerships will be lucrative.

Figure 2: A threat actor searches for partners, offering traffic from malicious campaigns.

Figure 2: A threat actor searches for partners, offering traffic from malicious campaigns.

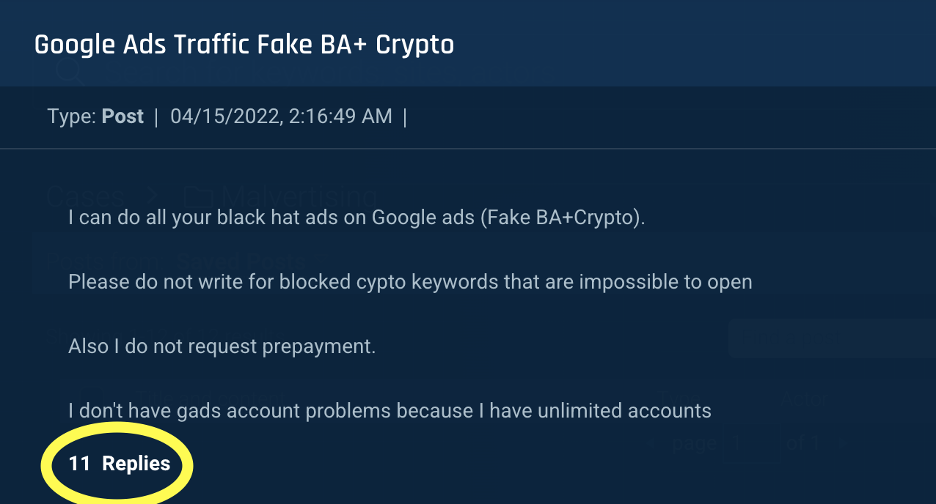

As shown in the example below, service providers often provide multiple services, offering Google Ads malvertising services and fake bank accounts (“Fake BA”).

Figure 3: A threat actor offers black hat services for Google ads

Figure 3: A threat actor offers black hat services for Google ads

Figure 4: A threat actor offers black hat services for Google ads

Figure 4: A threat actor offers black hat services for Google ads

In the following example, a service provider commented on a public post. In some instances, service providers also leave their contact information.

Figure 5: A service provider leaves a comment for another threat actor searching for malvertising services

Figure 5: A service provider leaves a comment for another threat actor searching for malvertising services

Service consumers

While a high percentage of cybercriminals have enough knowledge of software engineering to build malicious websites and applications, many lack specific malvertising expertise or knowledge of black hat SEO to direct online traffic to malicious content. Therefore, threat actors search for short- and long-term partnerships with malvertising service providers.

Figure 6: A team searches for a Google ads trafficker

Figure 6: A team searches for a Google ads trafficker

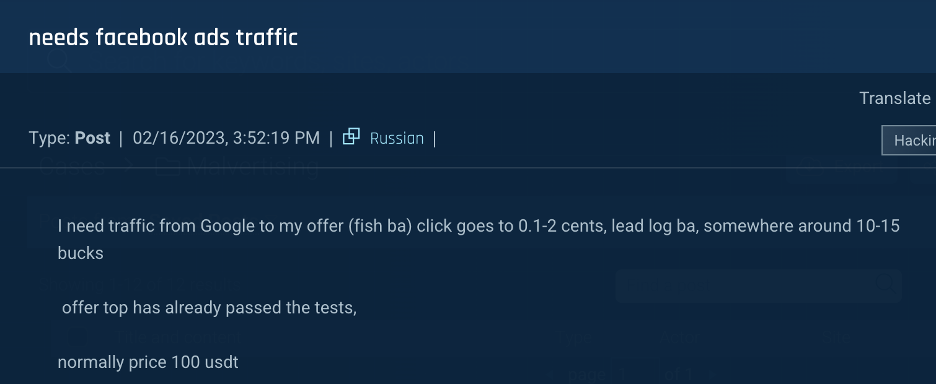

Figure 7: An actor searches for Google and Facebook fake ads services

Figure 7: An actor searches for Google and Facebook fake ads services

Figure 8: An actor searches for a Facebook ads service for his fake bank account

Figure 8: An actor searches for a Facebook ads service for his fake bank account

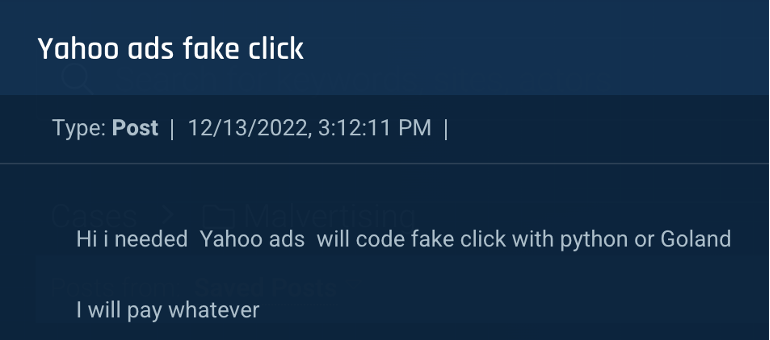

Figure 9: An actor searches for a Yahoo fake ads service

Figure 9: An actor searches for a Yahoo fake ads service

In other cases, threat actors specializing in fake ads and creating traffic seek partners who can provide content, such as phishing and scam pages.

Figure 10: A team seeks ad publishing services

Figure 10: A team seeks ad publishing services

Conclusion

Online advertising fuels the business models of some of the world’s largest companies, which invest heavily in ensuring that their users maximize ad views. As a result, it’s no surprise that attackers seek to piggyback on these networks for malicious purposes. Without a doubt, ads directing traffic to malicious websites damage the integrity of legitimate ads and can deter viewers from clicking through.

To preserve the value and integrity of online advertising, it’s in the best interest of ad platforms to monitor underground trends and TTPs related to malvertising. Doing so will enable them to take stronger measures to detect and prevent malvertising, ensuring that their users will feel safe viewing and clicking on credible advertisements.

)

)

)

)